When discussing literature throughout history, names arise within any of the existing currents. We can easily recognize all the Greeks in the creation of classical drama, Edgar Allan Poe establishing guidelines for the structure of contemporary short stories in Romanticism, Oscar Wilde inaugurating his own aestheticism movement… And the examples could go on. It would be elementary to say that literature has been exclusively a terrain of men; however, that would not be true.

Women have actively participated in the creation of literature in all its genres. However, we must refer to the facts; their path was different. To be taken seriously, published, and recognized as writers was a struggle that women had to endure, just like in any other area of society – outside of the roles of mothers and caretakers of the home. In reality, it was only relatively recently that women entered the world of literature with all their strength. Even at this point, we encounter more obstacles, as Virginia Woolf aptly put it: “A woman must have money and a room of her own if she is to write fiction.”

Women generally live in societies where the most extraordinary success they can aspire to is finding a good husband and dedicating themselves to their families and homes. Perhaps, in recent times, it may also be possible to aspire to a job, as long as it does not take too much time away from “neglecting” the family. It might seem that this way of life is a stereotype, but it is a reality. Issues such as deciding to pursue their careers, seeking independence, writing… become acts of rebellion. They become things outside of the every day, something strange and even alien. Like monsters.

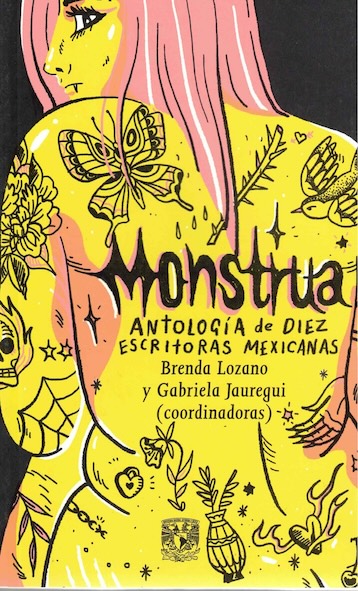

The monster created by Mary Shelley in Frankenstein reaches a revelation at some point: to lose fear and acquire power through it. That is what happens in this book. The anthology “Monstrua” talks about how the authors lose their fear of themselves and social repercussions and write. The coordinators choose “monstrua” instead of “monstruo” because, echoing Rosario Castellanos, even making that distinction is important: it’s something feminine. It’s women showing themselves, speaking out, writing.

This anthology offers texts created by young women from different parts of Mexico, from various contexts, communities, and languages, working in different genres such as poetry, short stories, essays, and even radio scripts. In addition, some authors present their texts in their native languages and provide translations into Spanish. Some of the texts are accompanied by photographs that not only accompany but also contribute to the atmosphere created by the text, enriching it and making it more intimate. Thus, readers encounter a proposal full of diversity, experimentation, and originality.

The work carried out by Brenda Lozano and Gabriela Jauregui as coordinators is not only dedicated and beautiful but also necessary. It is crucial for young women to see that what they have to say matters and that some means and people will seek ways to help them make their voices heard. These types of publications are what make a difference in the literary world because they present significant material, even collected from the most remote places in the country, demonstrating that there is still much more to discover.

Inkitt: BbyKevs

Wattpad: @SugoiKevs

TikTok: @bbykevs