On the rooftop of the UNAM Museum, the fourth edition of the kermesse “Editing the Everyday” took place today, Saturday, April 13th. Although it may sound unusual, it is precisely that: a kermesse. At the entrance of the museum, a stand was set up where people could get prints stamped on their skin like tattoos, serving as an invitation to go up to the kermesse, which was held on the rooftop. Upon entering the rooftop, attendees were greeted with hibiscus water and basket tacos. The event dynamics were explained, and “churru-pesos” bills were distributed, which could be exchanged for activities at the stands or items for sale, essentially serving as a welcome. The organizers of this event are 10 self-managed editorial collectives seeking to showcase their work as fanzine creators, while also creating a space to welcome both those familiar and unfamiliar with their work.

In Mexico, there are times of the year when, to commemorate special dates such as Independence Day and Mother’s Day, schools organize events called “kermesses.” These events are about socializing with classmates through games, activities, and sharing food. They were even more enjoyable when students were allowed to wear everyday clothes instead of uniforms, adding an extra appeal. Thus, the kermesse was the most “punk” moment of the year. For these fanzine creators, who know that the origin of the fanzine is rooted in punk culture, they have revived these two concepts to create “Editing the Everyday.”

The fact that it is a kermesse is not a coincidence; it is an idea developed by La Zinería and Editorial Mitote. They invite colleagues from the field whom they have met along their journey in editing and publishing. This journey has mainly been through bazaars and certain cultural events where, during social interactions, they noted that there are no spaces exclusively for them and their work as fanzine editors and independent publishers. So, not finding a place in book fairs or venues that open their doors to them, these collectives organize themselves and seek their own places for meetings and exhibitions.

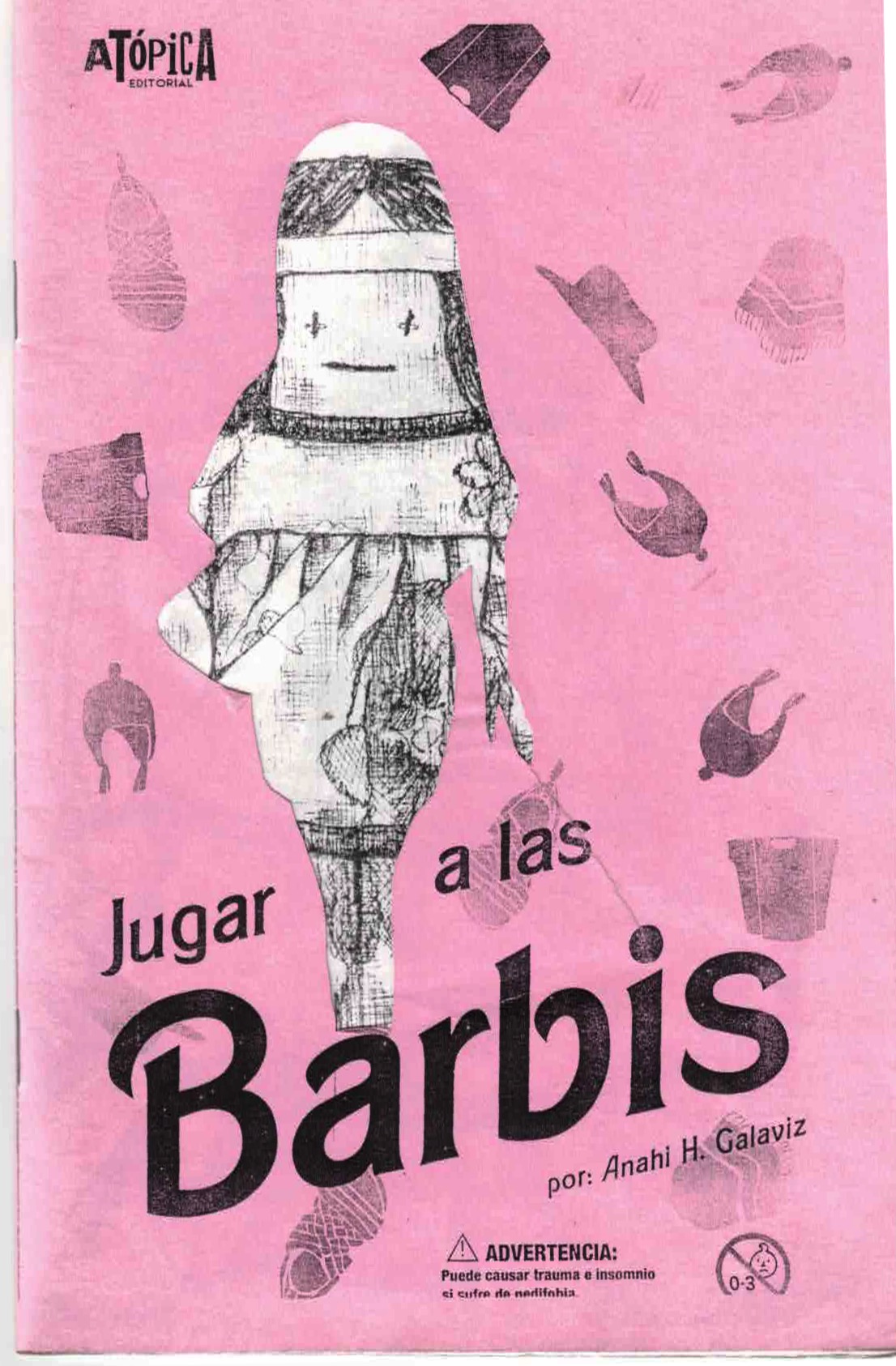

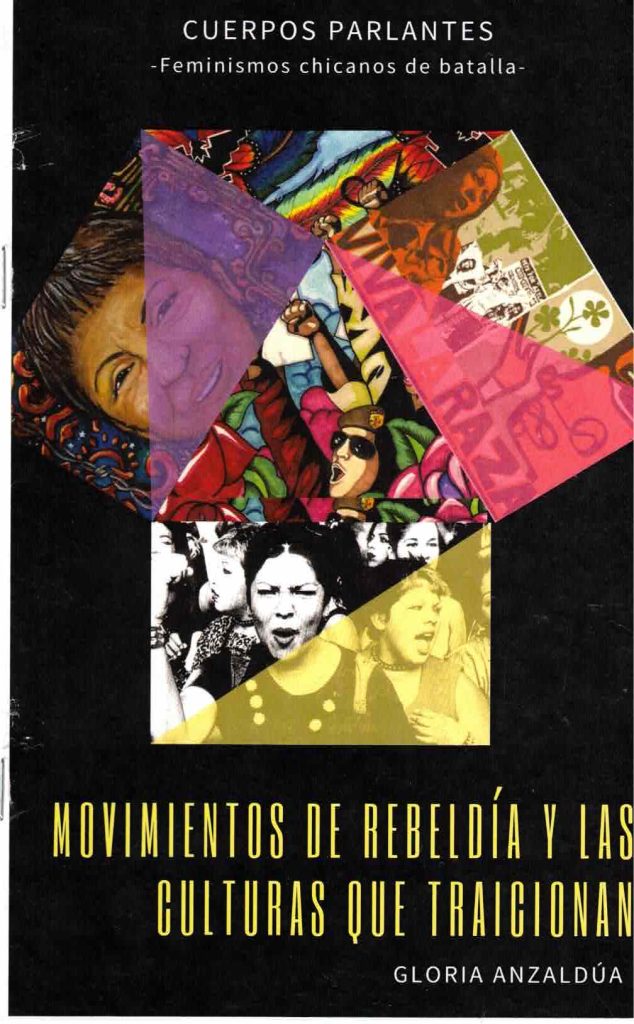

The artistic offerings ranged from fanzines to prints, illustrations, posters, newspaper figures, paintings, and items covered in epoxy resin. Additionally, there were talks, workshops, and readings in a room below where the kermesse took place. I came across titles such as “Cómo romper el corazón de un elefante” by Brian O’Brien, which narrates how elephants are kidnapped and separated from their herd to be trained and sold to zoos or circuses. Larissa Alcántara presented “¿A qué velocidad viaja el pasado que siempre nos alcanza?” where she discusses drug use during adolescence, packaging the fanzine in a plastic bag along with colorful stickers, small candies, and bead bracelets that resemble pills, thus creating an analogy to how drugs are packaged and presented. Baruck Racine created a photographic fanzine that tells the story of his life in the USA during his childhood, his life in Mexico, and how the border separating the two countries is not just physical. Additionally, the UNAM Fanzinoteca lent material for exhibition, which is part of their catalog that can be consulted at any time in their archival center.

The main idea of these collectives, besides showcasing their work, is to create spaces and build communities. They find it essential to break the stigmatization of what art should be and for whom it is intended. This particular vision arises because the creators have found that in their communities of origin, which they refer to as “the periphery”—Xochimilco, Ecatepec, Cuautla, Tláhuac, Morelos, Tlalnepantla—there is little openness to the graphic and artistic expression they produce. Few spaces have taken the risk in previous editions of this kermesse to open their doors and even fewer to finance them. Therefore, by joining efforts among collectives, they prepared an open invitation to the general public, creating an event where children are also welcome, offering young ones the opportunity to engage with this world and show them that there are people who make a living by “drawing pictures.”

@yolitzin_amantolli

@larissadeltiempo

@___existo___

Inkitt: BbyKevs

Wattpad: @SugoiKevs

TikTok: @bbykevs