Beyond the Myth: The Library of Alexandria

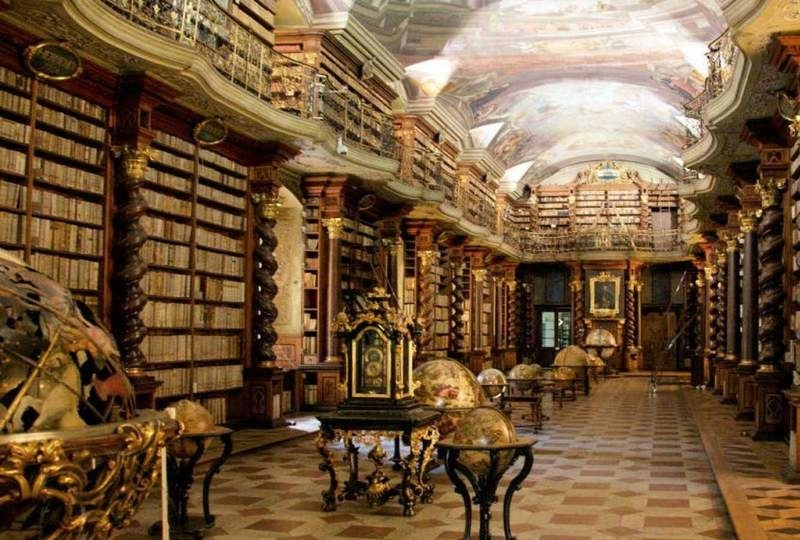

At some point in your life, you’ve probably heard of the legendary Library of Alexandria—even if just in passing. Words like knowledge, fire, history, and myth often arise when speaking of this ancient treasure. Whether you’re a curious reader or stumbled upon this blog by chance, here’s a look at how this place became one of the most famous libraries in human history.

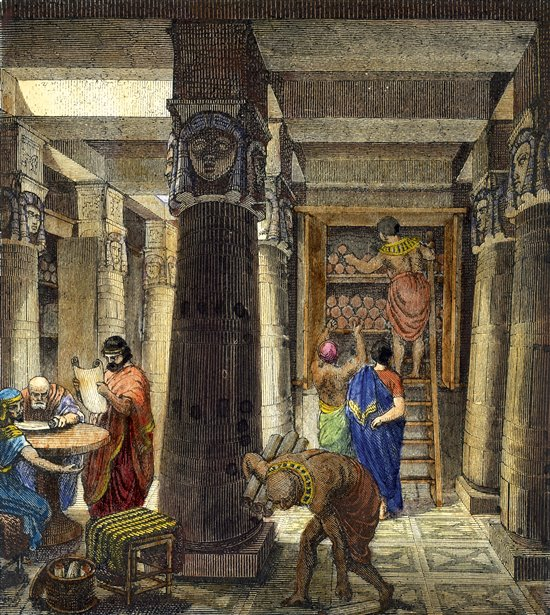

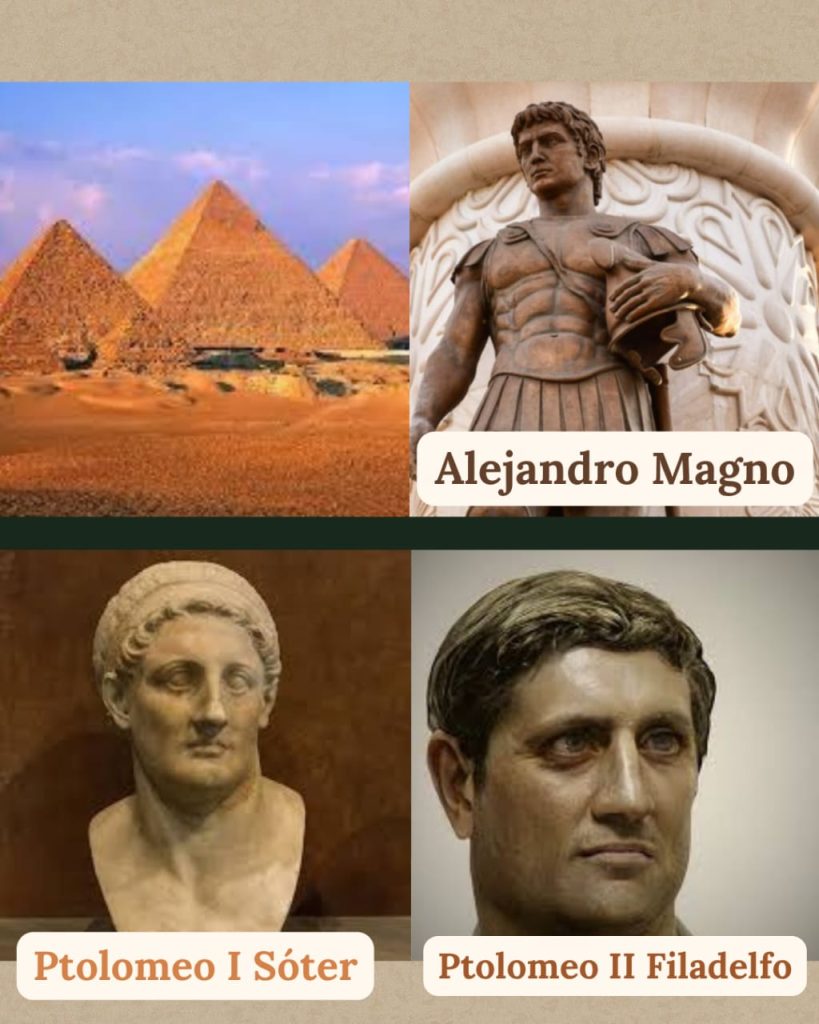

Let’s go back to Egypt around 300 BCE. While there’s a popular legend that credits Alexander the Great with the idea of a grand library, many scholars now believe it was actually Ptolemy I Soter who envisioned it, and that it was built under the reign of Ptolemy II Philadelphus. Thanks to the support of the Ptolemaic dynasty, the Great Library of Alexandria once housed between 40,000 and 400,000 works—some sources claim even more—including literary, academic, and religious texts, as well as Greek translations of key works from other languages.

This vast collection gave rise to the belief that the loss of the Library set back human intellectual progress by centuries. But how true is this? And what really led to its disappearance?

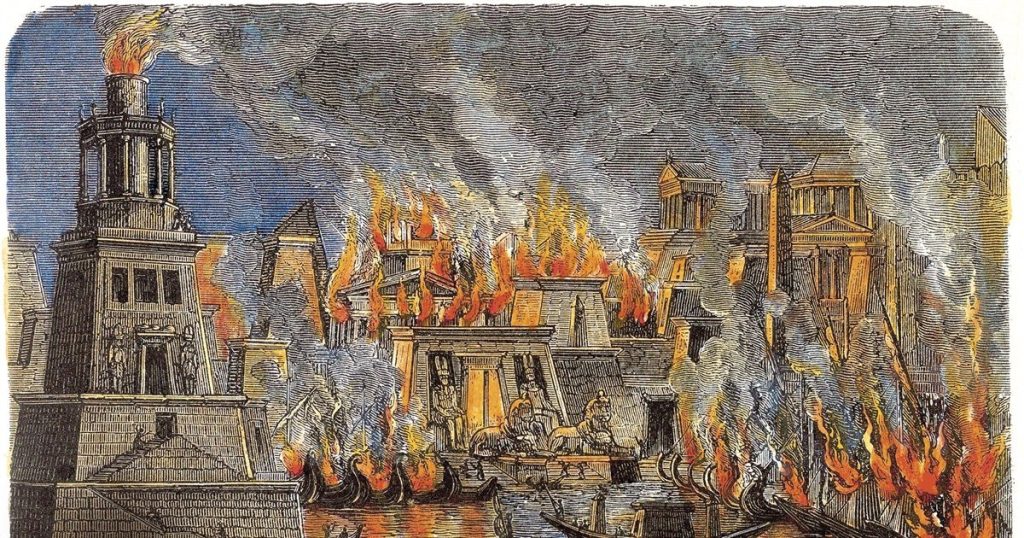

The most widely shared story is that the library was destroyed in a catastrophic fire. While a fire did occur, it wasn’t the sole cause of its decline. The Library’s influence gradually diminished over centuries. A major blow came in 145 BCE, when many intellectuals were purged from Alexandria. Then, in 48 BCE, during Julius Caesar’s civil war, the library—located within the royal palace—was accidentally set ablaze. However, there is debate over how much was actually destroyed. Some say the entire collection burned, but this seems unlikely, considering the size and location of the palace. But that’s not where the story ends.

After the fall of Antony and Cleopatra, Egypt—along with its Library—fell under Roman control. Without a royal court to maintain it, the Library began to fade. In the 4th century CE, with Christianity declared the official religion of the Roman Empire, the Library’s pagan knowledge became a target. Under Emperor Theodosius I, anti-pagan laws allowed Christians to destroy temples and institutions—possibly including what remained of the Library.

The so-called final blow came in 642 CE, when Muslim forces captured Alexandria. According to legend, Caliph Umar ordered the destruction of the library’s contents, arguing that if the texts agreed with the Quran, they were unnecessary—and if they contradicted it, they were heretical. It’s said it took six months to burn all the scrolls.

Yet, many historians believe this last tale is just that—a tale. By the time Muslim armies arrived, the Great Library of Alexandria had likely already disappeared. Most scholars agree it vanished gradually, falling victim to neglect, ideological shifts, and war.

The Library of Alexandria remains one of the most symbolic cultural losses in history—whether through violence, intolerance, or simple misfortune. It stands as a powerful reminder of how lucky we are today to have access to libraries and knowledge at our fingertips.

LITERATURE

Elia, R. H. (2013). EL INCENDIO DE LA BIBLIOTECA DE ALEJANDRÍA POR LOS ÁRABES: UNA HISTORIA FALSIFICADA. Byzantion Nea HelláS, 32, 37–69. https://doi.org/10.4067/s0718-84712013000100002

Hernández, D. (2020, October 24). La Biblioteca de Alejandría, la destrucción del gran centro del saber de la Antigüedad. Historia National Geographic. https://historia.nationalgeographic.com.es/a/biblioteca-alejandria-destruccion-gran-centro-saber-antiguedad_8593

Mark, J. J., & Games, M. (2023). Biblioteca de Alejandría. Enciclopedia De La Historia Del Mundo. https://www.worldhistory.org/trans/es/1-10883/biblioteca-de-alejandria/

escritores.org. (2020, June 1). La Biblioteca de Alejandría. Escritores.org – Recursos Para Escritores. https://www.escritores.org/recursos-para-escritores/recursos-2/articulos-de-interes/30203-la-biblioteca-de-alejandria

De Filología Clásica De La Universidad Complutense De Madrid, C. G. G. C. (2024, August 27). La batalla de Accio: Octavio derrota a Antonio y Cleopatra. Historia National Geographic. https://historia.nationalgeographic.com.es/a/batalla-actium_22155

Writer: Ortiz Lorena

Editor: Flores Nayivi