Considering Mexico as a tourist destination is always a good decision. It has beautiful beaches, cenotes, forests, towns, ancient civilization ruins, exquisite cuisine, and people who always welcome tourists warmly. On the other hand, living in Mexico City is an experience I would highly recommend. There is a mix of folklore, color, and tradition alongside the modernity of global technological advancements. In this city, there are many cultural and artistic offerings, numerous tourist attractions, and access to education. However, these two views are a bias that has been generated, perhaps because we tend to see the glass as half full. But the reality for those living on the outskirts of the city and those living in the provinces — not so far from the main tourist centers — is very different.

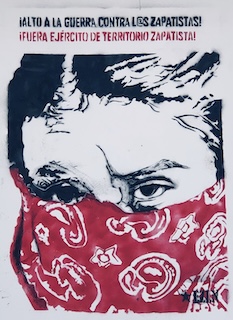

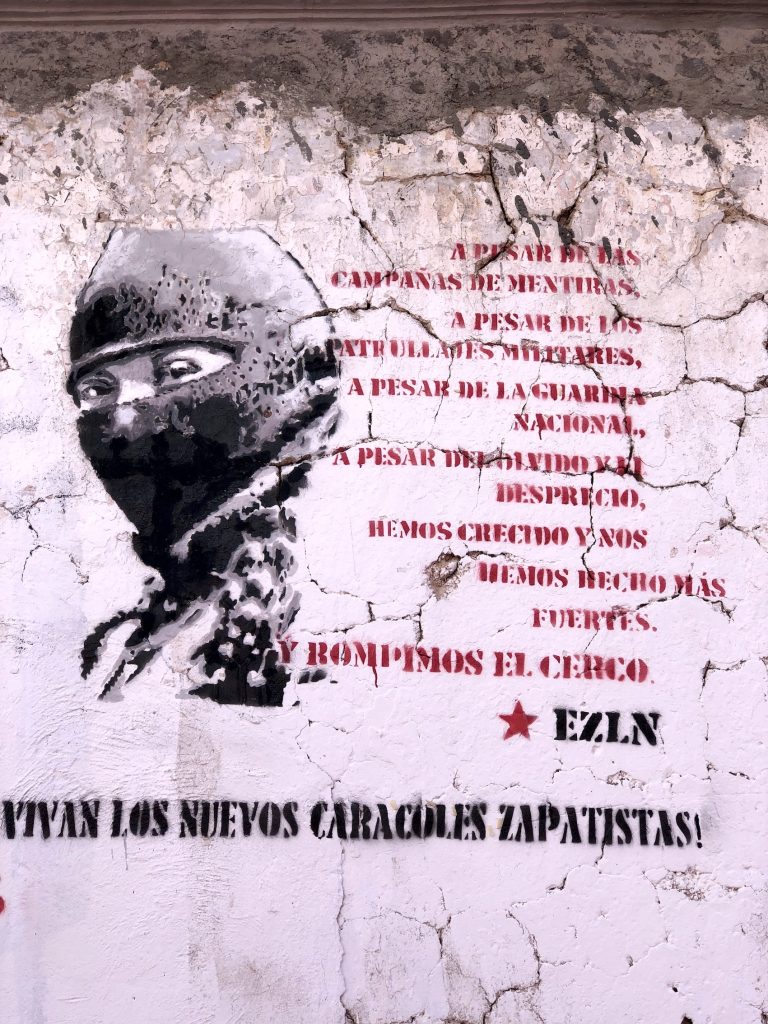

This movement began on the night of January 1, 1994, when the Zapatista Army of National Liberation (EZLN) staged an armed uprising in San Cristóbal de las Casas, presenting the First Declaration of the Lacandon Jungle: eleven demands—work, land, shelter, food, health, education, independence, freedom, democracy, justice, and peace. In essence, what they were demanding was as simple as it was fundamental: rights. These rights, which by the mere fact of being Mexicans, were already guaranteed by the laws established in the Constitution of 1917, but over the decades, they had been deprived of them or directly denied them. Who denied them these rights? Who marginalized the indigenous communities? The government could easily be partly responsible for this by not having the means to ensure the full exercise of their rights by providing roads and schools with adequate teaching materials, and establishing workplaces with fair working hours and wages, which in turn would allow them to access housing with water, sewage, and electricity services, as well as food and clothing. However, in this complex situation, there remains another actor to be named: the rest of society.

The modern society that adopted the customs of the conquerors lives in cities, speaks Spanish, and embraced a system that proposed neoliberalism as an economic model—a system that indirectly led to the EZLN movement. Although it is a society with many shortcomings and issues to resolve, it is not comparable to the precarious situation of most indigenous people in Mexico. While we are all Mexicans, the opportunities and contexts are not the same: indigenous communities have often been isolated and discriminated against for maintaining their customs and traditions, leading to them being seen as “the others.” This has created a separation that has only widened the cultural, economic, and political gap, culminating in the indigenous-peasant movement. This movement has had its flaws, like any autonomy, but it has maintained a legitimate struggle in the social aspect and has, in turn, inspired more similar manifestations.

The Latin American Council of Social Sciences offers readers a collection of books that aim to document the main movements, uprisings, and conflicts in Latin America and the Caribbean in the 21st century. Among them is this title, where the authors explain how, three decades after its inception, Zapatismo offers the most comprehensive, explicit, and radical version of indigenous-peasant autonomy known in the contemporary world. Thus, it becomes an essential read for understanding the current context of the countries in Central and South America.

Inkitt: BbyKevs

Wattpad: @SugoiKevs

TikTok: @bbykevs