Digital or Physical?

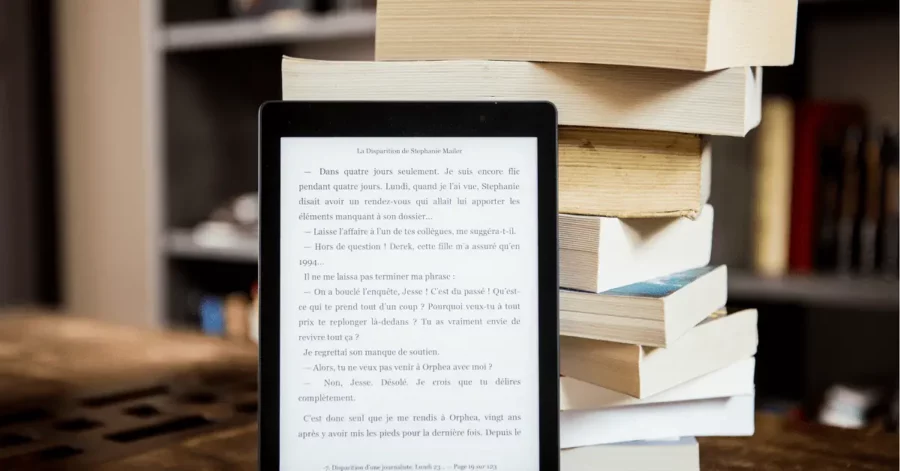

In recent times, when it comes to getting a book, one question has become increasingly common: digital or physical? Do I really want this book on paper, or can I settle for reading it on a screen? What’s better—feeling the pages in your handsor carrying an entire library in your phone, tablet, or Kindle?

It’s true: books take up space. Sometimes our homes aren’t equipped to store them properly—away from humidity, sunlight, and dust—to keep them in good condition. Otherwise, books quickly turn into worn, time-eaten objects. Many people choose to buy a physical book only after reading it digitally, knowing they might return to it again. On the other hand, many titles are hard to find in print, and that’s when digital books become our best ally.

But something curious has happened in recent years—we’ve become owners of nothing. Ever since music could be downloaded from shady websites—and more recently streamed on Spotify and similar apps—CD sales have dropped dramatically. Remember how major record stores used to sell out new albums in a day?

It’s the same with movies—we pay for seven streaming platforms, only to find the movie we want isn’t on any of them. Even personal memories like photographs are now just pixels stored on our phones—precious birthday or concert memories that vanish if the device gets wet or lost.

Personally, I prefer to own what I love. I want to rewatch a movie without searching through sketchy websites, or listen to music ripped from CDs without worrying about data or signal issues. And with books, it’s very similar. Beyond the unique joy of smelling the pages and touching the paper, it’s well known that reading on paper is better for your eyes and has been shown to improve comprehension compared to digital reading.

That said, eBooks let you highlight freely, take margin notes, look up definitions, increase font size, and read without a lamp—making them more convenient, practical, modern, and often more accessible.

Ultimately, there’s no single “right” way to read. What matters is finding what works for your time and lifestyle. The most important thing? To read. Because no matter the format, what truly matters is that a part of us stays in those words—and a part of them stays with us.

So, digital or physical? You choose. Just choose to read.