When we hear the history of our country—whatever it may be—we often think of it as something that happened to other people, in another life, something distant not just in time but in space. At times, it seems like it never happened at all. It’s normal to find it difficult to imagine how the world was before we knew it as it is today; even connecting our own present with our own past can be challenging, as much—if not everything—has changed since childhood. Hence the importance—and the human need—to leave a mark of our existence behind, to tell stories, to seek to endure. It’s a natural inclination. In many towns in Mexico, the custom of passing down history, customs, and traditions through oral storytelling persists.

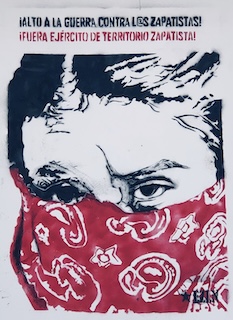

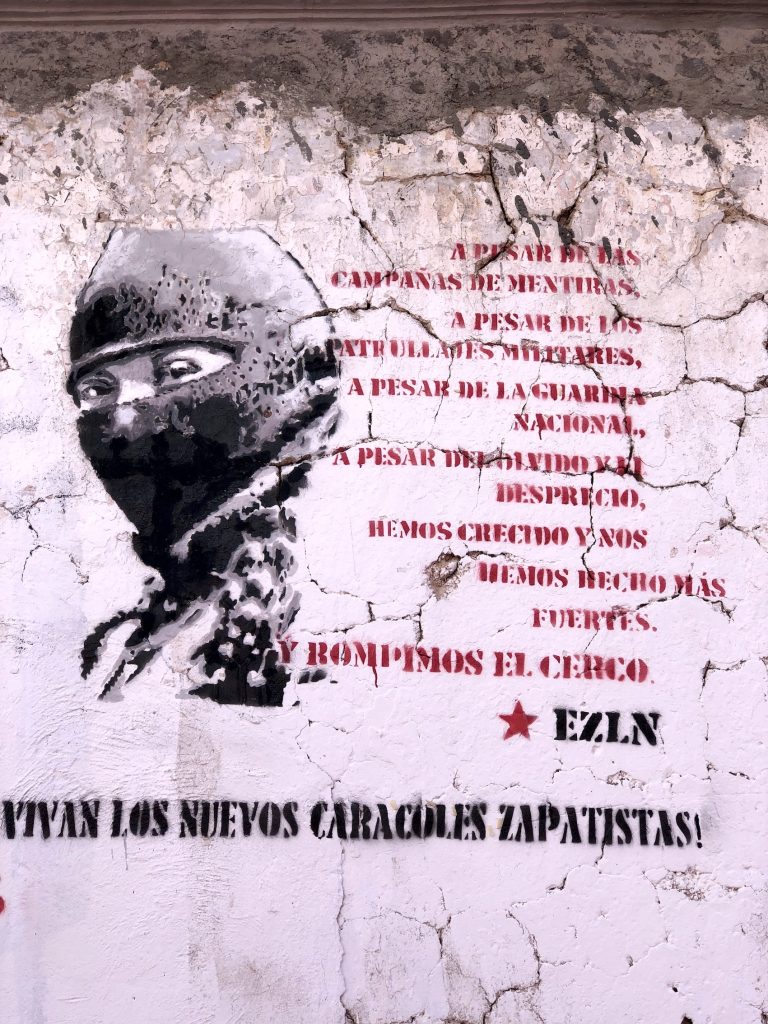

In a poorly told story, we can all be “the villain,” just as when we tell our version, we’ll always be “the hero.” However, regardless of being “good” or “bad”—which is highly subjective—the truth is that history, as written in books, is portrayed from the perspective of the victors. Understanding other perspectives of an event becomes challenging when we can only ask the deceased. Asking Emiliano Zapata about the revolution would be impossible (though wonderful to hear), which is why today he has become nothing less than a symbol. The ideological legacy he left behind is so powerful that after more than 110 years, his slogan “Land and Liberty” continues to be the rallying cry for those who still rebel against a system that oppresses them.

For those who have had an interest in delving deeper into history, in digging beyond what public school books offer, they have discovered that the southern leader was more than just a man interested in power. It’s said that when he sat in the presidential chair—without seeking any kind of title—he said to Francisco Villa, seated beside him, “And this is what they fight over?” But that could well be just an urban legend. What this title offers is something much more genuine and real: it’s the story of someone who was there, a man who in his youth was a Zapatista.

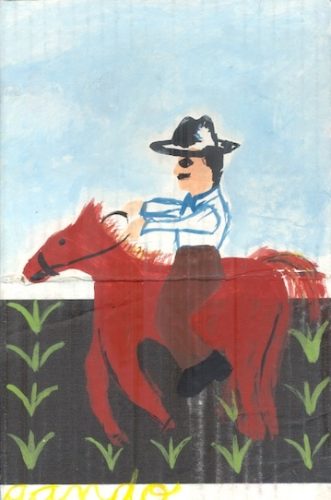

“And Zapata Keeps Riding” is a short story aimed especially at children, written by Victor Hugo Sánchez Reséndiz and published by La Cartonera. The narrative is simple yet captivating from the first page due to its authenticity, themes, and passion. Sánchez Reséndiz recounts the story of his grandfather, who used to tell children who approached him how it was to fight alongside Zapata, the reasons they did it, what life was like before, and how it was after the Mexican Revolution. He also tells them about the true fate of the leader and how he didn’t die as history says but went to Arabia, because he’s coming back to fight for freedom. This is what brings beauty to the story: the intimate aspects, the moments exaggerated for the sake of the narrative, the pride with which it’s told.

Although increasingly distant, the past is something that shapes our existence. It’s necessary to be able to reconcile with the past we have as a nation, to honor our origins, and to make peace with the dark episodes that have fallen—as they do for everyone—in our country. When we can do that, we can leave the past where it belongs and look towards tomorrow. And it’s important to clarify that leaving the past behind is not about forgetting it; on the contrary, it’s about acknowledging it. In recognizing it lies the rescue of stories like this one, valuable because they are part of the everyday; because the world has not been built only by the names that appear in books but by all the people who accompanied them, like Sánchez Reséndiz‘s grandfather. This title is filled with nostalgia, tender descriptions of Morelos and its people, but especially with tradition.

Inkitt: BbyKevs

Wattpad: @SugoiKevs

TikTok: @bbykevs