5 Great Books to Gift (or Treat Yourself) This Christmas

December is a month filled with wonderful things: the weather, the food, gatherings with family and friends, and, with the New Year around the corner, the chance to embrace what many consider a “fresh start.” And with new beginnings come new reading plans for the year ahead. Personally, I’m one of those who enjoy finishing any pending books before the year ends, just in time to map out a new reading journey. With this in mind, and to share both the holiday spirit and a love for Mexican literature, I’ve selected five titles that should definitely make it onto your reading list.

1. El murmullo entre las viñas de Diana Heredia

“My book reminds readers that no matter what happens, life always offers a chance to start over,” says the author about her work. Narrated from three perspectives, the story begins with Valeria, the protagonist, then shifts to her husband Julián’s point of view, and concludes with the voice of the Guadalupe Valley itself. This novel is known for its richly descriptive narrative, transporting readers to the scents, cuisine, and wines of the vineyards in Baja California.

2. Bazar nocturno de Carlos Iván Sánchez

This book is a collection of fantasy literature short stories, infused with humor and poetry. Combining two genres—short stories and microfiction—the author crafts characters and settings with just a few sentences. In the longer pieces, there’s an echo of Edgar Allan Poe’s style. Written over four years, this collection marks the author’s literary debut.

3. Country music de Edgar Trevizo

This poetry collection is divided into five sections, framed by a prologue and an epilogue that give it the feel of a complete narrative. Inspired by nature, small details, and the people of contemporary life, these verses also reflect the author’s cultural depth through reinterpretations of works by other poets.

4. El crimen de Mariana Jobs de Maileth Patiño

This short, mystery-filled novel follows Mariana, a professional accused of orchestrating the murder of her father, whom she never forgave for abandoning her. With her brother’s support, she fights to prove her innocence, only to encounter an unexpected twist that changes everything. Intrigue and suspense drive this modern tale.

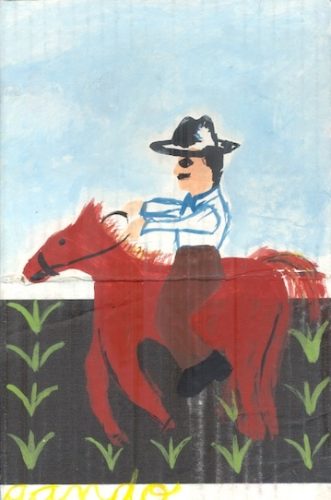

5. Antología de Lambert Schlechter

For the first time in Mexico, renowned Luxembourg poet Lambert Schlechter publishes a collection of 79 texts, including letters, poems, and reflections. This bilingual edition, in Spanish and its original language, showcases the richness of the text while being beautifully presented with handcrafted binding by La Cartonera, complete with a one-of-a-kind hand-drawn illustration.

Choosing the perfect gift can be a challenge, but these books bring intrigue, mystery, love, beauty, and humor. With such a wide variety of themes and styles, they’re perfect for giving—or keeping for yourself—this holiday season.

nkitt: BbyKevs

Wattpad: @SugoiKevs

TikTok: @bbykevs