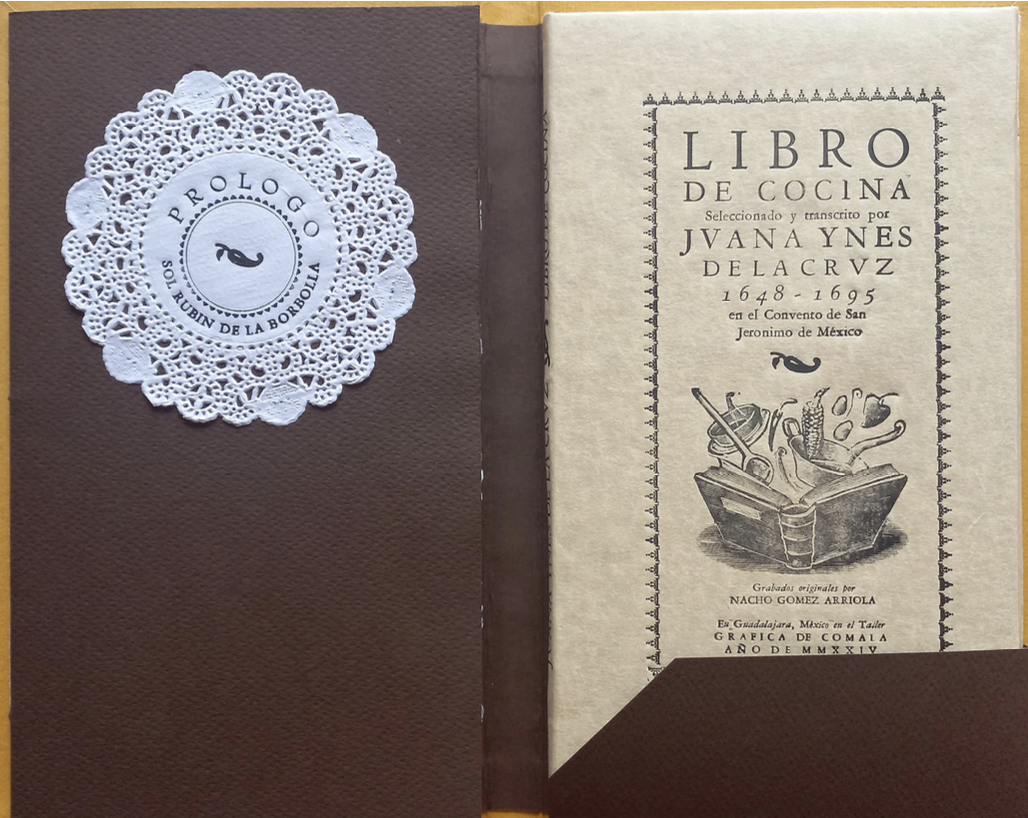

Some of my fondest childhood memories are rooted in the bookstores of Miguel Ángel de Quevedo. I vividly remember spending hours in the children’s book section, captivated by the illustrations—particularly those from A la orilla del viento, my favorites—while my parents browsed for their next reads. Despite being the last in my class to learn to read, within a month, I was reading faster and better than any of my classmates. Of course, this filled me with pride, but it wasn’t my ability to read that sparked my love for books. It was those long afternoons in the bookstore, often during May’s rainy season—when the weather was more predictable and May always brought showers—combined with the aroma of coffee wafting through the air, and the freedom my parents gave me to choose books without question, that won me over to reading.

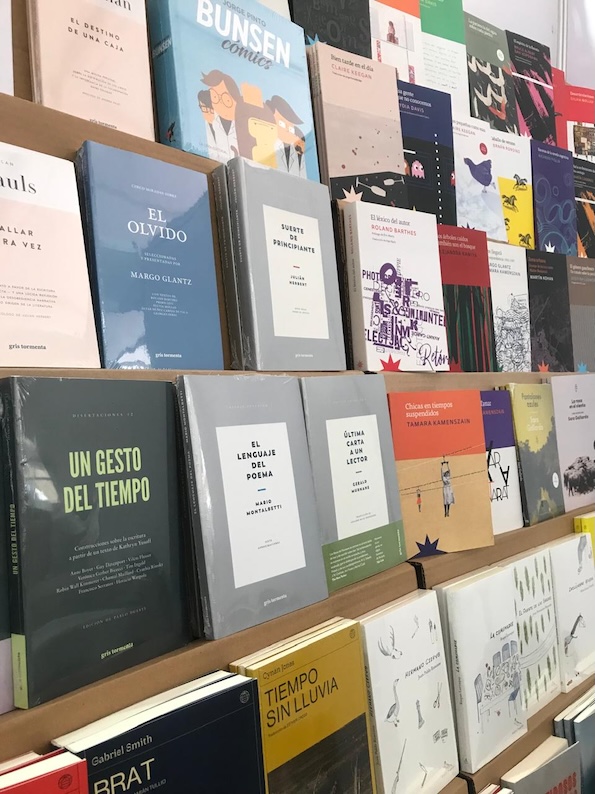

I’ve never fought against this love for books; instead, I’ve embraced it wholeheartedly, particularly through book fairs. This year, for example, I was captivated once again at the Feria Internacional del Libro Infantil y Juvenil 42 (FILIJ 42), held in the first section of Chapultepec Park. I find this location perfect—it’s ideal for a stroll through the city, a picnic, and, of course, browsing books. While the event primarily targets younger readers, it’s an excellent opportunity for adults to explore the latest youth literature. This not only allows us to understand younger generations through their literary preferences but also to enjoy the sheer joy of diverse reading. Some titles are enchanting for their design alone. For instance, I was amazed by “Tener un patito es útil” by Isol, a seemingly simple book with an interactive twist: two synchronized stories culminating in a heartwarming ending.

The fair also emphasized interactivity in its spaces. For example, Mango Manila created a cozy, child-friendly stand with tables and chairs for kids to read comfortably. Meanwhile, Combel Editorial featured a padded floor where young children could sit and flip through books safely. Across the stands, numerous activities catered to all ages: workshops, dramatic readings, circus acts, and concerts. One standout was La Perra, blending clown artistry with chamber rock in a family-friendly performance.

I strongly advocate for including youth literature in our regular reading habits. Sometimes, we dismiss these books as not offering intellectual value, but exploring beyond our comfort zones enriches our perspectives. This year’s FILIJ 42 also showcased graphic novels, a format growing in popularity. I was lucky enough to meet Logan Wayne, who shared his creative process behind “Semana inglesa”, a profound exploration of existential questions about whether we are truly where we want to be or merely where we think we should be.

Not everyone’s first encounter with books is as joyful as mine. In Mexico, reading is often seen as a chore rather than a delight, due to how it is introduced. Events like FILIJ are vital for changing this perception. For children, these fairs can create a positive, lasting impression of books; for teens, they offer a wide range of options to discover their path in reading. And for everyone else, it’s a chance to reconnect with books—or simply enjoy a lovely day in Chapultepec Park.

nkitt: BbyKevs

Wattpad: @SugoiKevs

TikTok: @bbykevs